| |

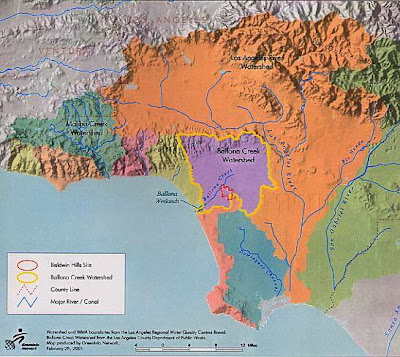

| Map of the Ballona Watershed and Wetlands in relation the general Los Angeles area. Source: www.ballonacreek.org |

Historical and Current Images of Ballona Wetlands:

|

| The current image of the Ballona Wetlands and Creek. Source: Friends of Ballona Wetlands. |

Historical State of Ballona Wetlands:

Ballona Wetlands are located at the mouth of Ballona Creek that drains into the Pacific Ocean at Santa Monica Bay. The US Environmental Protection Agency concludes that based on the T-sheet map produced by the US Coast Survey, Ballona Wetlands historically encompassed approximately 2,120 acres of land, an area over two times larger than today (12). The wetland’s hydrologic cycle used to be highly dynamic which made the presence of various interdependent habitats possible around the area (12). Without human interference, it enjoyed a natural tidal flow and “maintained both open and closed connections to the ocean as a function of the annual precipitation and other watershed variables” (12). This fertile land drew a tribe of Native Americans called Tongva to settle down about three to five thousand years ago (2). Their hunting and gathering lifestyle didn’t stress or drastically alter the wetlands. However, this kind of harmony between human and nature would soon be interrupted. Around 1820, a rancher called Augustine Machado acquired this big parcel of land through a land grant and decided to practice cattle grazing on the precious wetlands (2). In the middle of 1800s, farming replaced cattle ranching and became the major agricultural activity in the area (12). The Ballona Wetlands began to suffer and degrade from these land intensive agricultural practices. The health of the wetlands was further threatened as railroads and roadways were constructed from the late 1800s to early 1900s (12). As a result, the wetlands became more closely linked to the greater Los Angeles metropolitan area and much more accessible than before. The convenience provided lured large-scale real estate development to Venice and Playa del Rey, which gradually ate away the wetlands (12). Soon afterwards, oil exploration and extraction claimed the spotlight after the discovery of oil around the area in the 1930s. The wetland was put under even bigger stress due to these human activities. In 1935, Ballona Creek was channelized as a flood control measure, yet it resulted in “limited flow to the wetlands and lagoons, drying them up” (12). Alteration of habitats which resulted from the change in drainage pattern is permanent, which means loss of species is inevitable. The construction of Marina Del Rey in the late 1950s was devastating for the Ballona Wetlands because dredge spoils produced during the construction were carelessly dumped into the wetlands (10) and more than “900 acres of wetlands were destroyed” (2). Only about 200 acres were left after the construction, the smallest size it has ever been (12).

Current Human Impacts on the Ballona Wetland:

The fate of Ballona Wetlands changed at the turn of the century. After the state acquisition of the wetlands in 2004, around 600 acres were put under protection (12). The California State Coastal Conservancy provides funding for developing restoration projects (12). In the same year, a new tide gate was constructed which not only helps better control floods but also allows a more natural tidal flow to the wetlands, a critical condition for a healthy wetland (2). The increase in tidal flushing brings back wildlife that has once left Ballona; the endangered Least Tern and Belding’s Savannah Sparrow are among the species that have returned to the wetlands (2). The California Department of Fish and Game is actively working with the California Coastal Conservancy to develop a restoration plan for the wetlands (9). Other than these government agencies, non-profit organizations, such as Friends of Ballona Wetlands and The Ballona Wetlands Land Trust, play important roles in educating the public about the important ecosystem services wetlands have, instilling environmental stewardship, and advocating for the protection and restoration of Ballona Wetlands (1 and 2). Since Ballona Wetlands are surrounded by highly urbanized areas, the wetlands are greatly impacted by human activities: as suggested in a 2006 study, storm water runoff that gets contaminated as it runs through these urban areas ultimately drains into the wetlands through the Ballona Creek and significantly increases the fecal indicator of bacteria of the wetlands (9). The condition has significantly improved since then. It’s shown that due to pollution management efforts, lower concentration of FIB is found in Ballona Creek in a 2010 study than the 2006 study (6). It’s expected that as contaminated runoff continues to diminish, the wetlands can function primarily as a sink of FIB instead of alternating between sink- and source-mode as it is today and are able to purify water before it drains to the Santa Monica Bay (6).

|

| The pie charts show the change in habitat composition in Ballona Wetlands. Source: Southern California Coastal Water Research Project. |

Future Prospects of the Ballona Wetlands:

|

| The map shows the percentage of invasive species present in different areas of Ballona Wetlands. Source: "Existing Habitat at Ballona Wetlands: Areas A and C" by David W. Kay. |

The Ballona Wetlands are the only remaining

coastal wetlands in Los Angeles County and one of the most valuable habitats

for rare and endangered species in Southern California (1). Historically, the wetlands have reduced extensively over the last

hundred years due to a number of reasons, such as widespread cattle grazing and

the development of Marina del Rey. However, despite the declining conditions,

the future prospects of the Ballona Wetlands are looking up with great

possibility for improvement over time. This is because of the push in recent

decades to protect the Ballona Wetlands ecosystem and reestablish endangered

species specific to the area through the help of restoration projects.

Different organizations, such as the Friends of Ballona Wetlands and the

Ballona Wetlands Land Trust, are continuously aiding in the restoration efforts

by organizing volunteer restoration events every month and engage participants

in hands-on restoration of the unique and rare coastal habitat at Ballona. The

Friends of Ballona Wetlands’ award-winning volunteer Restoration Program

provides the opportunity to restore this precious coastal ecosystem while

learning about its value (2). Similarly, the Ballona

Wetlands Land Trust also organizes volunteer events and also asks the public to

participate in public meetings and comment on the work being done and progress

being made. The restoration projects will require collaboration from

governmental agencies, non-profit organizations, and volunteers alike in order

to maximize the beneficial effects of this work. Additionally, the Earthways

Foundation has also pledged to support the preservation and restoration effort

by helping expand public awareness, meeting with public officials, and

coordinating activities among other groups. California has lost 95% of its once

extensive wetlands, primarily to residential and commercial development

(11). In the future, the Ballona Wetlands will greatly

benefit from these restoration projects, which will help to preserve the

ecosystem and reestablish some of the rare and endangered species. However, the

progression of the restoration may be slow and may not always be successful in

rebuilding certain species which rely on specific habitats. Nevertheless, while

some of these species no longer occur in coastal Los Angeles County, those that

do should be afforded special consideration in future restoration efforts

(7).

Suggestions for the Future:

In order to

further progress the restoration work being down to improve the Ballona

Wetlands ecosystem; it is important to underscore a few key strategies that

will maintain the current positive human impacts and minimize any further

degradation. First of all, one of the strategies would be to properly maintain

the tide gates in order to control floods and insure a more natural tidal flow

into the wetlands. Furthermore, it is also important to acknowledge the native

bird species that have reestablished on the wetlands and support their specific

habitats, thereby stabilizing their return. Additionally, in order to further

minimize degradation of the wetlands, there should be more regulation to manage

pollution and prevent contamination from urban runoff. Another suggestion to

further restore the Ballona Wetlands would be to progressively remove

non-native species in order open up niches and help in the reestablishment of

native species. The Ballona Wetlands are the only coastal wetlands in Southern California

and need to be protected from any further degradation. Although more efforts

will be needed to restore the Ballona Wetlands to its natural states, the

outlook is positive as long as people continue to protect this ecosystem.

Reference List:

- Ballona Wetlands Land Trust. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

- Friends of Ballona Wetlands. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

- Kay, David W. “Existing Habitat at Ballona Wetlands: Areas A and C.” Marina Del Rey Patch. N.p., 24 July 2013. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

- “Project: Science to Support Regional Wetland Assessment and Uncertainties in Wetland Restoration.” Southern California Coastal Water Research Project. 19 Sep. 2011. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

- Cohen, Tamira, Shane S Que Hee, Richard F Ambrose. “Trace Metals in Fish and Invertebrates of Three California Coastal Wetlands.” Marine Pollution Bulletin, 42.3 (2001): 224-232. Print.

- Dorsey, John H., Patrick M. Carter, Sean Bergquist, Rafe Sagarin. “Reduction of Fecal Indicator Bacteria (FIB) in the Ballona Wetlands Saltwater Marsh (Los Angeles County, California, USA) with Implications for Restoration Actions.” Water Research. 44.15 (2010): 4630-4642. Print.

- Cooper, Daniel S. “The Use of Historical Data in the Restoration of the Avifauna of the Ballona Wetlands, Los Angeles County, California.” Natural Areas Journal. 28.1 (2008): 83-90. Print.

- Groves, Martha. “Lawsuit Is Filed over Proposed Interpretive Center at Ballona Wetlands.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, 15 Sept. 2013. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

- Dorsey, John H. “Densities of Fecal Indicator Bacteria in Tidal Waters of the Ballona Wetlands, Los Angeles County, California.” Southern California Academy of Sciences. 105.2 (2006): 59-75. Print.

- Ballona Wetlands Restoration Project. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

- “Ballona Wetlands Protection.” EarthWays Foundation, n.d. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

- United States. Environmental Protection Agency. Ballona Creek Wetlands Total Maximum Daily Loads for Sediment and Invasive Exotic Vegetation, 2012. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment